“Accountability is not a bad thing, but it can be done badly. And that’s where we find ourselves now…No single idea, policy or solution can begin to address all the challenges in 50 states, 15,000 districts and 90,000 public schools…we need accountability for the entire system.” — Dennis Van Roekel, President of NEA, 6/10/14

Accountability in ESEA reauthorization needs to take into account all the major issues involved in student performance.

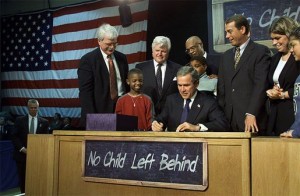

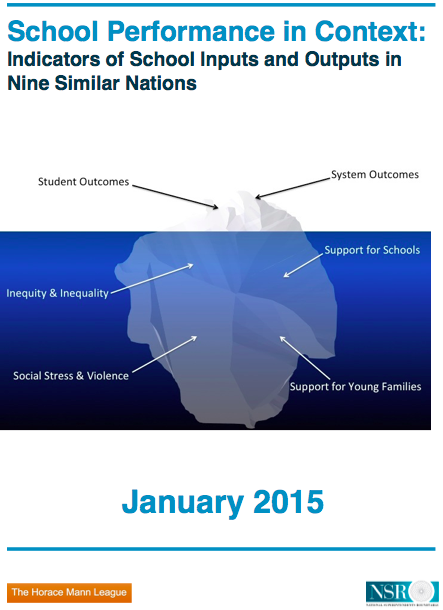

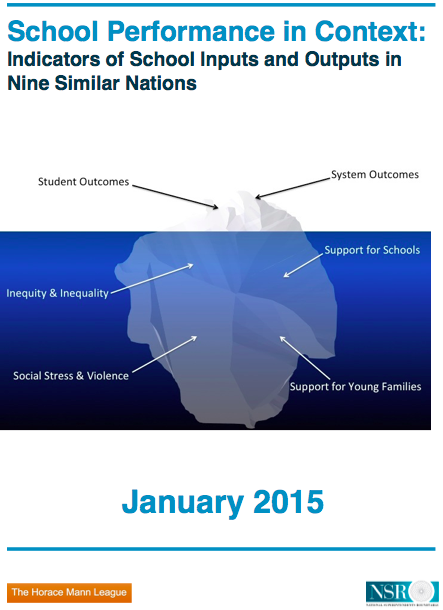

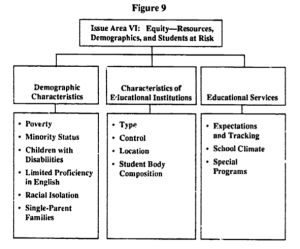

When you look at the visual provided here, it’s easy to see that our myopic focus on student outcomes as the basis of accountability for No Child Left Behind set us on a tragic course destined to sink the U.S. education system.

To attempt an explanation of how accountability for the entire system is possible, I elected to begin with a statement from this, October 28, 2014, letter from key civil rights organizations.

To: President Obama, Secretary Duncan, Congressional and State Educational Leaders:

Re: Improving Public Education Accountability Systems and Addressing Educational Equity.

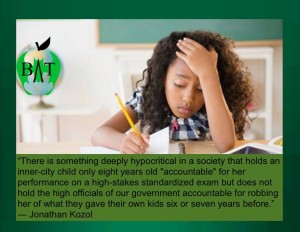

“…many struggling school systems have made little progress under rules that emphasize testing without investing.”

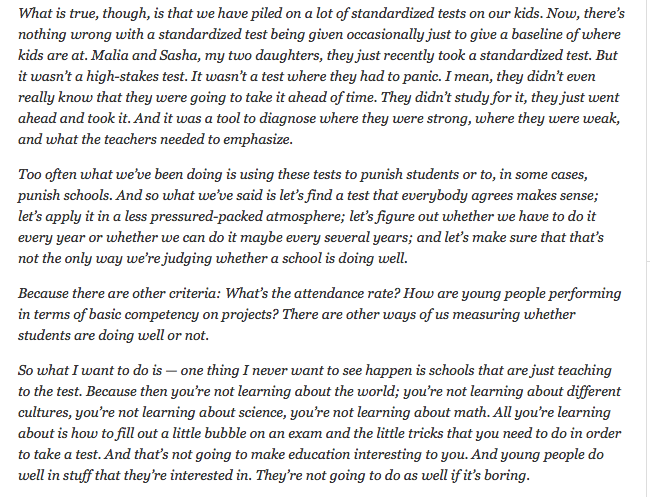

The focus on “testing without investing” can very simply be brought to a halt. If the government won’t stop this, parents will have to take the law into their own hands as they are doing with the United Opt Out Movement.

The focus on “testing without investing” can very simply be brought to a halt. If the government won’t stop this, parents will have to take the law into their own hands as they are doing with the United Opt Out Movement.

If those continuing to insist on forced yearly testing are doing so because they do not trust state and local officials to work towards equal opportunity, that is understandable. But IF Congress cannot “fix” their mistakes now, after being aware of them for a decade, a two-year federal moratorium on all federally mandated testing except NAEP (National Assessment of Education Progress) is reasonable given what we know.

We know we created a lost generation in education and in our economy. We tested without investing in real school improvements. We ignored much while focusing only on the tip of the iceberg.

Here’s the problem:

“Common sense dictates that in order for students to achieve they must have appropriate opportunities to learn.” Wendy Schwartz – Opportunity To Learn Standards, 1995

The concept of “opportunity to learn assessments” isn’t something that the public hears much about but as Schwartz explained, they are “used to indicate overall educational quality, and, more specifically, the availability and use of education resources.”

Hopefully that helps people better understand the concerns of the civil rights groups and their requests to Congress and the Obama administration. The eight points below are theirs; the elaboration on them is mine. Their emphasis was on providing “productive learning conditions for all students in each school” using measures of educational inputs and outcomes based on eight requirements for effective accountability:

- Appropriate and Equitable Resources to ensure opportunities to learn,

- Multiple Measures of both inputs and outcomes,

- Shared Responsibility – from the community to the classroom to all levels of the system – to fulfill their obligation to support learning for all students,

- Professional Competence requiring proper preparation, continuing education,and professional learning opportunities for all,

- Informative Assessments that are indicators of continuous improvement of both the students’ progress and the systems’ responsiveness to identified problems,

- Transparency requiring that the indicators of improvement be specific, targeted, meaningful, and easily accessible and readable,

- Meaningful and Responsive Parental and Family Engagement must be made a priority in funding and practice,

- Capacity Building should be the focus of all interventions whether it is for the student, school, or system because it is only by strengthening and increasing an individuals’ or institutions’ capability to perform that we ensure a strong foundation for progress.

HOW?

The structure for a responsive and responsible accountability mechanism was recommended in 1991 by the Special Study Panel on Education Indicators and presented to the Acting Commissioner of Education Statistics, Emerson J. Elliott, then Secretary of Education Lamar Alexander, and Assistant Secretary of the Office of Educational Research and Improvement Diane Ravitch.

The panels’ goal was to “develop a comprehensive education indicator information system capable of monitoring the health of the enterprise, identifying problems, and illuminating the road ahead” which meant they were looking at leading indicators as well as an evaluation of the systems’ current status.

The panel began by clarifying that “unlike most other statistics, an indicator is policy-relevant and problem-oriented…but indicators cannot, by themselves, identify causes or solutions.”

Understanding that “information requirements of the federal government have little in common with those of the school superintendent or principal,” the panel anticipated the need for indicator systems corresponding to federal, state, and local needs.

Their first step was to define “the conceptual framework” and “fundamental principles” by which to create and guide an education indicator information system to meet the demands of the public and policymakers.

These fundamental convictions were outlined and explained:

- Indicators should address enduring issues. We should assess what we think is important, not settle for what we can measure.

- The public’s understanding of education can be improved by high-quality, reliable indicators.

- An effective indicator system must monitor education outcomes and processes wherever they occur.

- An indicator system built solely around achievement tests will mislead the American people.

- An indicator system must respect the complexity of the educational process and the internal operations of schools and colleges.

- Higher education and the nation’s schools can no longer be permitted to go their separate ways.

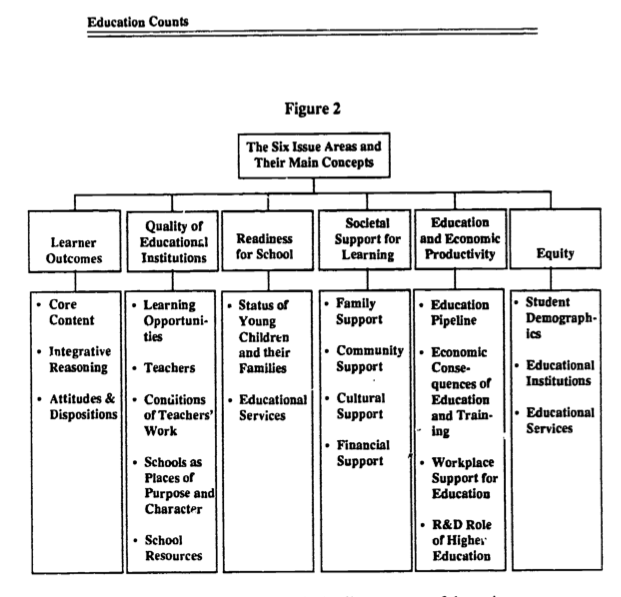

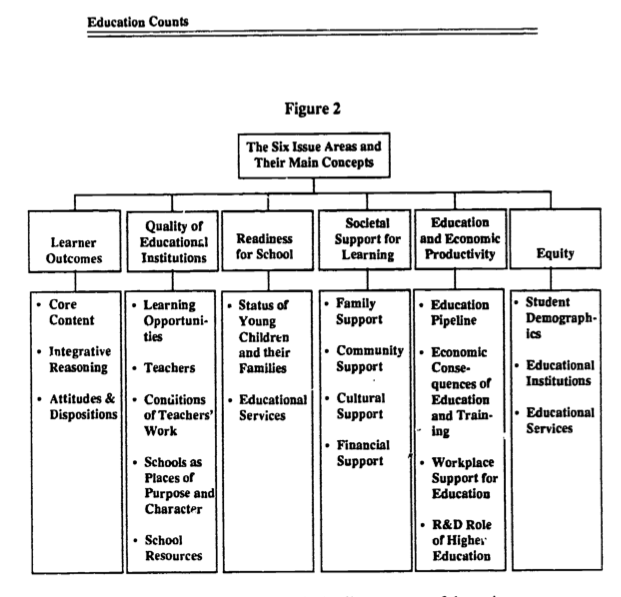

The panel set down a framework around six issues and the main factors contributing to success in those areas. They expressed the concept as “clusters of indicators” designed to give us the best understanding of these complex issues. In essence, this panel was encouraging us to develop a “mixed model of indicators — national indicators, state and local indicators, and a subset of indicators held in common.”

In essence, this panel was encouraging us to develop a “mixed model of indicators — national indicators, state and local indicators, and a subset of indicators held in common.”

But — always a “but” — in 1991, the public and this panel still held the belief, and clearly pushed it forward, that international comparison data was “the ultimate benchmarks of educational performance.” It wouldn’t be until 1993 that a brief glimpse at the Sandia National Laboratories report on education put the interpretation of international test scores, and standardized test scores in general, in perspective. “The major differences in education systems and cultures across countries diminish the value of these single-point comparisons.”

Sandia researchers critically evaluated “popular, not necessarily appropriate” measures of performance and in the end stated that the available data was collected for such “specific purposes” that it was “often used in unintended and sometimes inappropriate applications.” They warned, “this practice may result in poorly focused actions, with disappointing outcomes.” On that point, both of these groups of researchers were in agreement.

To avoid too narrow a focus yet not be overwhelmed by statistics or the collection of them, the 1991 Panel on Education Indicators went for a “comprehensive” issue-focused approach.

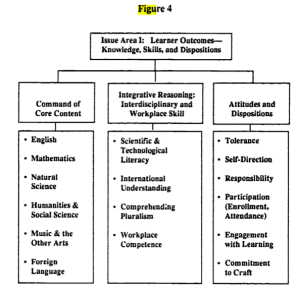

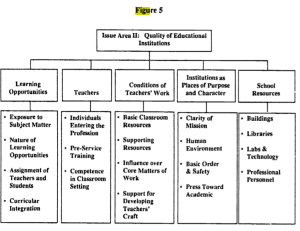

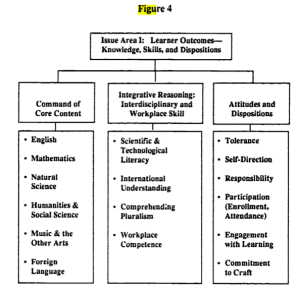

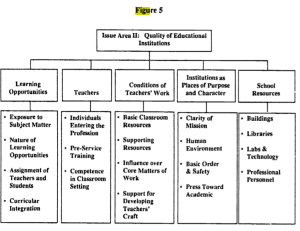

For each of the six issue areas, they further detailed the system with subsets.

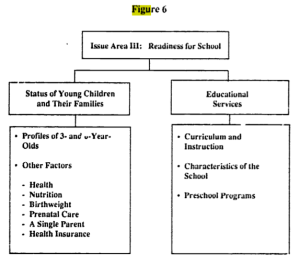

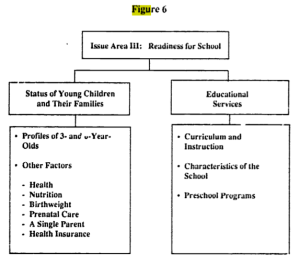

They did the same with issues of “leading indicators” particularly changes in society affecting a child’s readiness for school…

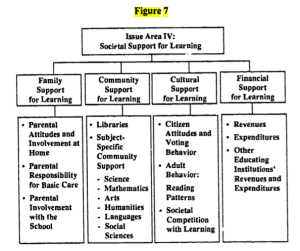

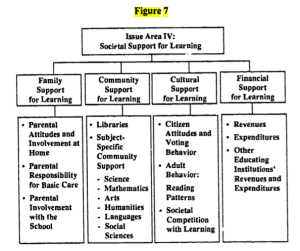

…and the supports necessary for student success.

The panel stressed that “the most powerful system of indicators will start from the perspective of what consumers and the public expect and need from education” understanding that “the people of the United States also clearly expect the nation’s schools and colleges to advance certain national values above and beyond the benefits education provides to individual students.”

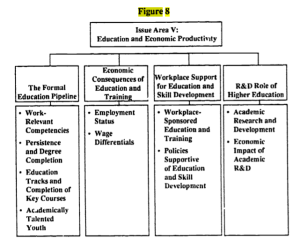

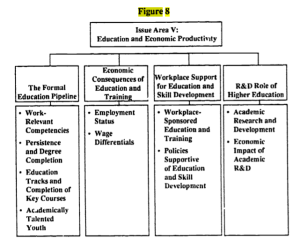

To accommodate the public, these two issues were included: education and economic productivity, and…

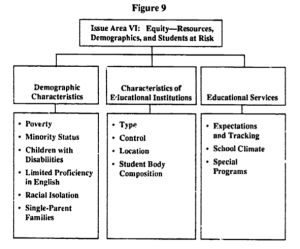

… equity in American education.

Is this doable? Could a “mixed model of indicators” be used to assess all the elements laid out in the civil rights letter? For our large and diverse country, would this system better fit our needs than the test-based accountability of No Child Left Behind?

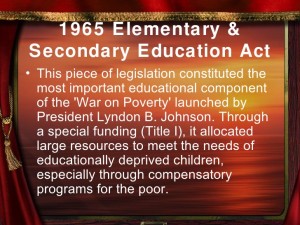

The original Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) was NOT an accountability law until the No Child Left Behind version of it. ESEA was one of a group of anti-poverty laws.

Do we want to return ESEA to its original goals? Should accountability be set nationally in a manner such as outlined here, but, maybe under its own law? Now would be the time to decide.

What we know with certainty is that current federal education law, as it stands, has neither served us well nor protected children from the harmful effects of politics-gone-wrong.

Our lawmakers have proven themselves incapable of responsible decision-making in the arena of education policy. It is time for the People to make demands.

Choices to consider: 1) Push Congress to make the law right, 2) call for a moratorium on testing if they can’t produce a reauthorization we can live with and prosper by, 3) boycott testing now. Unfulfilled promises of action are no longer good enough.

PARENTS: submit your tests refusal letters now. The parents that came before you in the standards, testing, accountability movement waited for lawmakers to act. They didn’t; you must.

CITIZENS: what happened to leaving a place better than you found it? The public education system is systematically being dismantled. Get off the sidelines!

To read more about accountability at the different levels, see Accountability Where It Matters Most, Accountability for School Quality, and Accountability for Administration.

We aren’t short on ideas; we are stymied by the corrupted politics of education.

Update 5/6/2015 PLEASE view the accountability summary chart now under the Federal Education Law drop down menu. Thank you for considering.