The education reform oligarchy of the 80’s had a school choice conversation —at least one that is a matter of record.

The education reform oligarchy of the 80’s had a school choice conversation —at least one that is a matter of record.

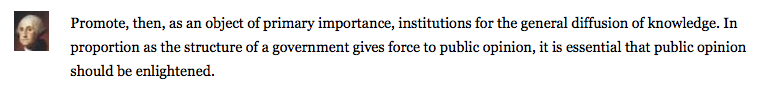

It’s doubtful that the public can recall what was discussed. It’s doubtful that very many were really invited to listen. What is more likely is that most people are left asking, what school choice conversation?

So here’s how the story went…

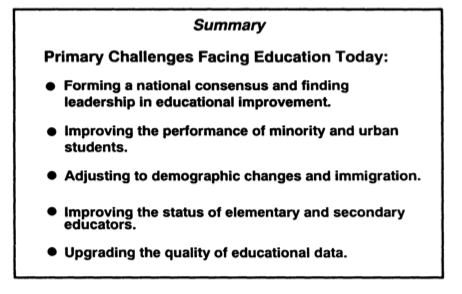

“At its meeting in August 1985, the members of the National Governors’ Association [NGA] formed seven task forces for the purpose of examining in-depth critical problem areas in American education.”

It’s unlikely that very many people would argue against the idea that parent involvement in education is critical. Then — now, forever, and always — parent, community, and national involvement and support for public schools is a problem in critical need of being addressed with real solutions. How exactly school choice came to be seen as a “critical” problem depends …

“Whether the push for school choice is driven by economic and political forces, or by parents and educators, depends on whom you ask.”

What we know for sure is now our history.

To be clear, since the development of free desegregated public school education, people in the United States of America have had the freedom to choose between their local public schools, private schools, and home-schooling. There is no forced attendance at government-run schools only. There are compulsory attendance laws to protect a child’s right to an education but people have always had a choice in how to comply with that law. We have always had school choice. … to date.

But when was it discussed that school choice is the best answer for a lack of parental involvement? Who knows?

What was decided was to attach the issue of school choice to that of parental involvement. However, at the 1986NGAAnnualMeeting, a year after the topics had been decided, then Governor Lamar Alexander introduced the topic like this…

“We will then hear presentations from three of the Governors who led the task forces on teaching, on leadership, and on choice.”

Their presentation of a critical problem area went from “parental involvement and choice” to “choice”?

Governor Dick Lamm of Colorado chaired that task force. As he explained it,…

“What we were looking at is how can we give additional flexibility to parents and students in choosing their schools within the public school context.”…

“Some of these could be magnet schools, some of them could be alternative schools, some of them could just be different options among the public schools.”

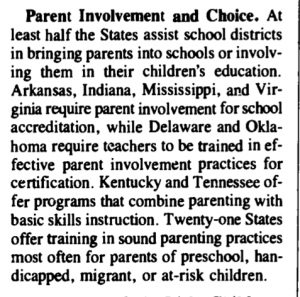

Lamm recommended PUBLIC choices. These choices were all under local district governance. And even though the topic was introduced as “choice,” Governor Lamm did share some views on parental involvement.

And he did acknowledge…

“The two things we looked at: choice, parental involvement. They are related but they are also separate.”

But in publication after publication, parental involvement and choice would be lumped together without any emphasis on “the choice” being “within the public school context.” It was never a significant part of the school choice public conversation.

The chair of the Choice Task Force wasn’t the only one voicing concerns.

Mr. Al Shanker (then head of the American Federation of Teachers) was one among many who tried to explain the potential pitfalls of “choice.”

“We live in a society where that [choice] is one of our top values.”

“Kids have more of a commitment when they decide on a program or a school than parents do.”

“I am very concerned, and I think all of us have to be concerned, that there are situations where choice could result, let’s say, in the top 25 percent of the students in a major city being offered nice spots in suburban schools, and leaving the schools in that city that might very well be on their way to coming back, leaving them without any role models at all for those other students.”

“Therefore, as we move towards systems of choice, I think you ought to be very sensitive that we may be leaving a lot of kids behind, and we have got to look at that. That’s not to argue against choice, it’s just to argue that we do it in a thoughtful way.”

“There is one other downside which hasn’t been mentioned on this…. The parents’ associations in England complain bitterly that if you have the right to switch, nobody wants to fight. That is, nobody is left to argue that you need improvement in the school because the dissatisfied people move out, leaving only those who either don’t know what is going on or who don’t care, or don’t have the time or the energy to move.”

“You rescue your own kid and say the heck with the rest of it. These things have to be watched.”

“I don’t know all the problems that are going to arise….I want to experiment. I want to make sure we don’t decimate the cities.”

Was it just the teacher’s union and a governor or two that questioned school choice as a reform strategy?

Ms. Georgeanne Sherrill, a career ladder 3 elementary teacher in Tennessee, was attending the 1986 NGA meeting to present information on instructional leadership and “career ladders” — an initiative of Lamar Alexander’s. She joined the conversation (p.68).

“I would just like to say one thing. I think it’s in connection with what Ms. Futrell [then president of National Education Association] said. I think we can give parents a choice in education without having to pull the students out of one school and put them in another school. We can work with parents to structure the program in that school to meet the needs of the parents that have children in that school.”

That suggestion seemed to be discarded at the time but is finding favor in some areas of the country now.

So it wasn’t just one union leader, or two, or one teacher that voiced objections and concerns. As the chair of the Parent Involvement and Choice Task Force, Governor Lamm went on to explain…..

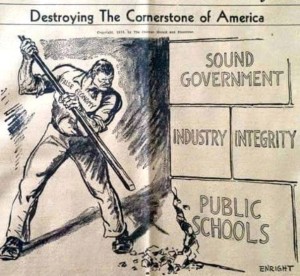

“I, like I think most of the other governors, are desperately concerned about opening up choice to public or private school and the choice of a voucher or any similar thing, with cannibalizing the existing public school system, about taking resources that are already really too limited.”

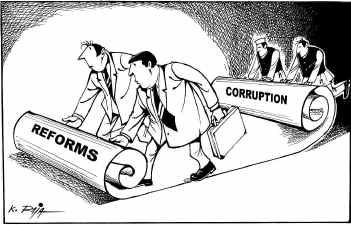

There was definite dissention in the ranks of leadership. But the dissenting voices were effectively struck down at every turn by then Secretary of Education Bennett and the Chair of NGA, Governor Alexander.

The conversation going forward? It was framed.

What did we hear from the chair of NGA? We heard the question,

“Why not let parents choose the schools their children attend?”

And the talk was of a “better schools movement.”

“It will mean giving parents more choice of the public schools their children attend as one way of assuring higher quality without heavy-handed state control.”

And the project moved forward with the help of the U.S. Department of Education under Secretary Bennett’s leadership. The nation had a new project, officially —Project Education Reform.

The critical problems of parental involvement and choice became joined at the hip —one dragging the other forward—but at this point in the story, not much was really said about the details of choice.

Did the report by the National Commission on Excellence in Education (A Nation at Risk) have school choice as one of its recommendations? No. The school choice agenda moved forward because influential and “gifted” people pushed it.

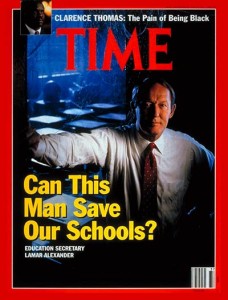

William Bennett was one such leader, for sure…

“He is a man of great brilliance and strong convictions, but he is a preacher, not a teacher. He is trying to manipulate public opinion to accept his ideas of what is right and wrong. This would be forgivable if he were not as gifted as he is and if he were not the Secretary of Education.”

”Bill Bennett is the first Secretary to understand the ideological and political possibilities of the office that were there from the beginning. In Bill Bennett we’re getting our first Minister of Education.”

“…he waded in with a controversial new voucher plan that would give parents of disadvantaged children funds that could be spent in private and parochial as well as public schools.”

School choice was part of the Bennett agenda from the beginning. How much he really cared about the disadvantaged, who knows?

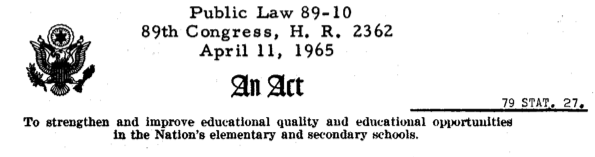

But by 1989, we had a new president, a different secretary of education, and had some changes in governorships. What did not change was the Project Education Reform agenda —with one exception. The facade of parent involvement had been dropped. Instead of a task force on Parent Involvement and Choice, we now had a working group for Choice and Restructuring (pg.44).

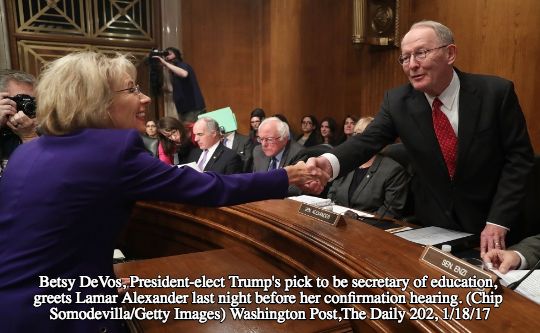

And by 1991, it was Lamar Alexander who became secretary of education putting himself in a prime position to carry their reform agenda forward.

And by 1991, it was Lamar Alexander who became secretary of education putting himself in a prime position to carry their reform agenda forward.

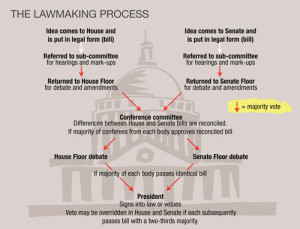

Today as head of the senate education committee, he has done his part to federalize the plan for school choice while being the artful dodger in avoiding any conversation concerning “choice.” The reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act is in conference committee…..tick, tock….

Time for the school choice conversation again? In light of the fact that the Dyett Hunger Strike is occurring in Chicago because an open enrollment neighborhood public high school is no longer a choice, we need to have the school choice conversation all over again…now. What is America’s choice?

“The hunger strike is now at Day 28 as of this writing (9/13/15) and the Chicago Board of Education has finally opened talks with the strikers.”

This level of sacrifice by a small group of people should make us all feel a bit humbled by their resolve, but a little sick inside that it has come to this — the oligarchy rules and, in general, they don’t feel the need to listen to any of us.

The public’s choice?

The public’s choice?