This question — do I understand ESEA? — should have been a starting point for President Obama and all 535 members of Congress as they approached the reauthorization of ESEA (Elementary and Secondary Education Act).

I’m only attempting to answer that question and others today because a citizen on Facebook asked.

ESEA is Confusing

ESEA —the original 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act — and NCLB (No Child Left Behind) are technically the same law but the similarities in their purposes and methods are few.

Here’s Senator Crapo (R-ID) understanding in 2015 used here to demonstrate some misunderstandings;

ESEA was actually enacted in 1965 and its focus was on funding to children disadvantaged by poverty. The funds were to meet under-privileged children’s educational needs through improved teacher, counselor, and state leadership training, community support services, and increasing support for libraries and learning materials.

“The provisions ended in 2007”?

That’s confusing. It sounds as if NCLB ended; it did not! Congress just FAILED at that point to do their jobs and review and rewrite it. So, the detrimental effects of the law continued unchecked for eight more years…..and beyond (see UPDATE below).

How ESEA Once Worked

To implement the original ESEA required low-income communities to identify the needs of impoverished children and develop plans to address those needs. This is because the focus of the law was on meeting the needs of “educationally-deprived” or “disadvantaged” children. This was the mechanism through which the original lawmakers envisioned offering poor children an equal shot at success in life, as best the public schools can.

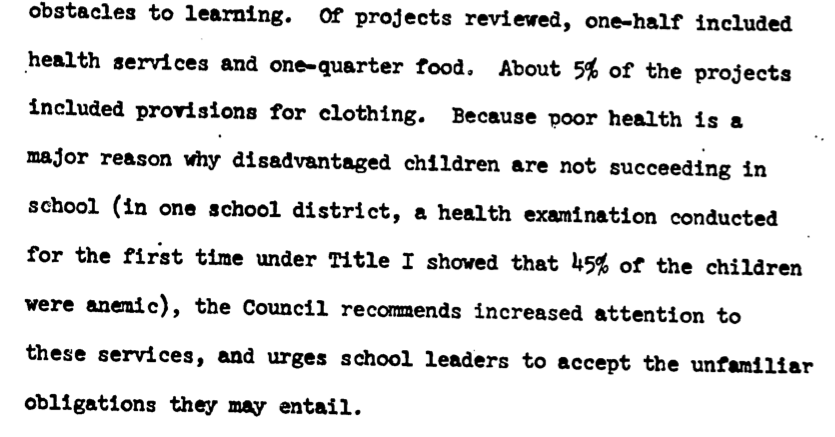

Less than a year after the 1965 ESEA was put into action, a committee reviewed the results and found that the dollars were being used in a variety of ways. … The 1965 ESEA was based on JFK’s vision.

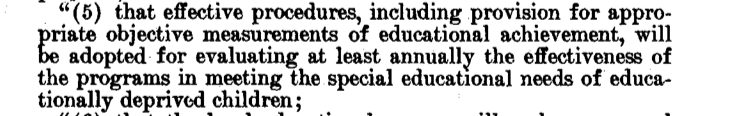

The 1965 ESEA was based on JFK’s vision. The “assessment” requirement was to prove the effectiveness of the school’s plans in meeting the needs of impoverished children. For example, the assessment of program effectiveness in decreasing the number of anemic children might include a variety of indicators (number of low-income parents attending adult nutrition classes, food distribution numbers, number of local nurses trained to educate new parents, final blood screening results, etc.). The assessment was to fit the program of improvement and the only mention of measuring achievement was this…

The “assessment” requirement was to prove the effectiveness of the school’s plans in meeting the needs of impoverished children. For example, the assessment of program effectiveness in decreasing the number of anemic children might include a variety of indicators (number of low-income parents attending adult nutrition classes, food distribution numbers, number of local nurses trained to educate new parents, final blood screening results, etc.). The assessment was to fit the program of improvement and the only mention of measuring achievement was this…

Were “achievement gaps” also monitored?

Yes, eventually, but not in this law. It wasn’t the main focus. Monitoring the achievement gap became more important when the U.S. Department of Education was created in part to ensure equal access to quality education. They then created the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), using it to monitor educational trends.

Facebook Question: Isn’t it true that schools are entitled to additional federal funding if they meet performance standards?

It’s not true of the original law. It is of NCLB because it stipulates punishing low-performing schools and reward high-performing schools based on a free-market model of competition. It is also true because of the way the system set up “grants” of money based on who has the best grant writers and can make their student population perform well on standardized tests, or if they can manipulate their data well.

This was not true with the original ESEA. ESEA’s funding focused on children from low-income families and an accounting of wise use of federal dollars. Districts receiving federal funds needed to demonstrate results based on an assessment of how well they were meeting the needs of children (inputs) as well as improving success in academics (outcomes).

Facebook Question: Does that mean that schools can ignore ESEA and continue on as before?

Schools in areas of concentrated poverty shouldn’t ignore their dependency on federal education dollars through ESEA. Many use those dollars wisely because they have honest, hard-working, knowledgeable leadership. Other places are narrowing the curriculum because they play the teach-to-the-test game. Unequal access to quality education persists for that reason.

Facebook Question: What is wrong with the government expecting performance for our tax dollars?

Absolutely nothing. But the misunderstanding in this nation is that “performance” on standardized tests equates to the quality of education and equal access to it. It doesn’t.

The truth is counter-intuitive. Standards don’t ensure achievement.

Standardized test scores continue to correlate most closely to a child’s socioeconomic status, which doesn’t usually change dramatically from year to year. Yearly testing of every student for purposes of judging schools from the federal level is an unethical use of standardized tests. Done randomly, NAEP test scale scores serve as a barometer of the achievement gap between rich and poor, black and white. (P.S. The gap narrowed most significantly in the two decades following the original ESEA.)

What should we expect in the way of accountability?

It’s appropriate to expect an accounting of how our federal tax-dollars are spend. But it needs to be more than a simple accounting. Long ago and repeatedly since, recommendations for indicators of resource inputs, parental and community supports, and a variety of outcomes were put forward in 1991. But overlooking better indicators of educational quality and access, lawmakers adopted standardized test scores instead.  These were great questions to try to answer! I’m so fortunate to have seen them. This is exactly the type of question/answer session the country needs to hear. It’s the only hope of getting ESEA reauthorization (and education reform) right.

These were great questions to try to answer! I’m so fortunate to have seen them. This is exactly the type of question/answer session the country needs to hear. It’s the only hope of getting ESEA reauthorization (and education reform) right.

Obviously regular people are asking the right questions. Meanwhile lawmakers remain ignorant of how poverty affects children and how federal education law can help improve the odds of each child having access to quality learning opportunities. We need to remedy that problem before Congress and the president reauthorize ESEA without correcting the mistakes made through No Child Left Behind.

(UPDATE: Too late. Congress & the Obama administration passed the Every Student Succeeds Act – ESSA – December 10, 2015. NCLB mistakes remain. More emphasis is now on privatizing public education through “charters.”)