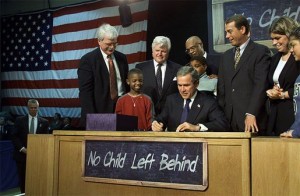

At the signing ceremony for No Child Left Behind (NCLB), President Bush joked, “I don’t intend to read it all.” But he was sure that in NCLB we would “find that it contains some very important principles that will help guide our public school system for the next decades. First principle is accountability.”

President Bush didn’t read NCLB before signing it. (How about your representatives?) That’s joke number one. Funny, huh? But what is even more amusing — sarcastically speaking— is trying to find where the word “accountability” was defined in the law. In laws and policies, key words are often defined so as to leave no doubt about the laws’ intentions. I word searched the desk copy and original. Didn’t find “accountability” defined. I could have missed it. Apparently, I wasn’t the only one.

NCLB says it will provide “greater” accountability; it will “increase” the accountability. How exactly this increase would occur based on the dictates of the law was always left to people’s imaginations and driven by emotions because, by God, we want someone “held” accountable for low school “performance.” And the country was led to believe that standardized tests for math and language arts would determine school quality— accurately. That fallacy would be joke number two.

As Bush declared a decade later, “it’s time to celebrate success [mission accomplished, eh?], but it’s also a time to fight off those who would weaken standards or accountability. I don’t think you can solve a problem if you can’t diagnose it.”

Standardized achievement tests don’t “diagnose” problems. They are only one indicator and because of their “nature,” yearly-standardized achievement testing is unnecessary.

It’s like taking an animal’s temperature and finding they have a fever. Yes, they have a fever but the thermometer reading doesn’t diagnose the problem.

New standardized tests, even so-called “better” tests, only give us information about a school at one moment in time with their given population — a snapshot. That snapshot changes slowly (unless you teach directly to the test). The most consistent finding (over at least five decades) is that standardized test results most strongly correlate to socioeconomic status (schools already have that personal data). More students from low-income families score lower on standardized tests— partially because of the nature of standardized tests.

I once attended a conference where one of the breakout discussions was led by a teacher from a neighboring community with a high-poverty, high-migrant worker population. Over the years, she had made the correlation that her students whose parents only spoke Spanish in the household would (on the average) score 20 percentage points lower on standardized tests.

Some could argue that this demonstrates the value of testing but the reality is, she knew this without the tests. And she didn’t need to keep proving it. She knew her students, knew their family’s background, observed the phenomenon, and test scores made no difference in how she went about teaching. The community situation was out of her control because of the lack of local authority to act on what WAS diagnosed as a problem.

She knew she had to do everything she could to properly educate her students. I know that from what the breakout was really about, how to teach English Language Learners. The test score discussion was an aside. Assessments and interventions designed to help students must take place in the classroom.

So, truth is, test results don’t necessarily give us a diagnosis. And certainly, as we know by now, accountability for math and language arts instruction alone does not make for a well-rounded education. The joke has been on us.

How many of these types of jokes will we take before we quit being amused?

Former President Bush went on to tell us that “people like [former school superintendents] Joel Klein and Michelle Rhee, people who are willing to challenge the status quo, tell you that one thing that made it [NCLB] effective was the accountability.”

Whoa! Klein – former chancellor of N.Y. city schools – and Rhee – former chancellor of D.C. schools – say NCLB accountability made their schools “effective.” We had better ask them to define THAT word. And ask this dynamic duo why they were so central to developing new standards (Common Core) and tests while turning their backs on other needs in their communities. In 2009, were their school districts adequately funded? By what measure did they make that call? Where’s the accounting? If their schools were so effective, why did they push their Smart Options agenda in 2009?

Genuine accountability for educating America’s children is both a shared responsibility and a national necessity because the public has and is demanding it. The only rational way to satisfy the People’s demand is to make it right by using what we know.

No Child Left Behind yearly mandate for nation-wide testing of math and language arts for the purported purpose of “accountability” misled the nation. (That requirement is unchanged in the NCLB replacement called the Every Student Succeeds Act that was signed into law on 12/10/15.)

No Child Left Behind “accountability” was a cruel joke. There is a better way.