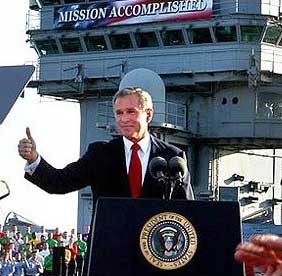

Our modern-day standards movement can roughly be marked by the release of A Nation at Risk in 1983. And “standards” crept into federal law under George H. W. Bush with the help of Assistant Secretary of Education Diane Ratvich who promoted the use of “academic” standards.

We use descriptors of every kind when we talk of standards: academic, performance, process, content, curricular, core, opportunity-to-learn, and always “higher.”

But let’s talk about how to use standards. As Charles M. Reigeluth explained in “To Standardize or to Customize Learning?”—“If not properly conceived, standards can do far more harm than good….They can be used as tools for standardization—to make all students alike. Or they can be used as tools for customization—to help meet individual students’ needs”

We can look at it this way: There is no standard way to drive; there are rules, there are guidelines, but when it comes to getting behind the wheel, it’s an individual thing with decisions made based on variables. Reigeluth provided this —“To use a travel analogy, standards for manufacturing are comparable to a single destination for all travelers to reach, whereas standards for education are more like milestones on many never-ending journeys whereby different travelers may go to many different places.”

Who chooses the road for our young travelers?

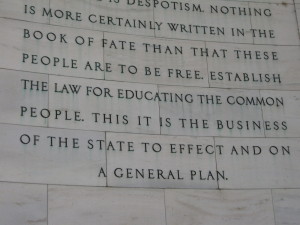

As long as we offer all of our education traveler’s quality opportunities along the way, we have fulfilled the promise of equal opportunity. But we have not.

The process for using standards is not simple. It seems reasonable to have content standards developed in cooperation with experts in the content areas; that is where “experts” can help “locals.” And after that (again quoting Marzano & Kendall,1997) “standards-based approaches must be tailor made to the specific needs and values of individual schools and districts.”

So, the Mid-continent Research for Education and Learning (McREL) regional educational laboratory long ago developed a data base of content standards along with advice on how to use them to develop classroom curriculum to meet the needs of the community. My advice is to use what we know.

This controversial and divisive topic of “standards” comes down to the fact that we can take a “content” standard, which is a description of what the student should know and be able to do (as defined by experts in a given subject) and turn it into a “curriculum” standard which takes into account how a subject is best presented along with suggested activities. This produces a usable instructional framework.

Ultimately, what is “best” for students in any given classroom can only be decided right there in the classroom, in real time, with much prior planning. This is a starting point in the travel toward excellence.

But we must be clear — standards for academic achievement are not the same as standardization of instruction.

And as was pointed out in A Nation at Risk, standardized tests of achievement should be “administered at major transition points from one level of schooling to another and particularly from high school to college or work.”

We sure as shootin’ blew that advice to hell and back!

Part 6 of ten blogs on The Road to Educational Quality and Equality that started with The March Begins.