Republican political analyst and writer David Brooks’ spoke about Character and The Common Good last week in Boise, Idaho. His conflicting views on the importance of community versus our current education “reforms” were striking — to me.

Brooks spoke about how love, relationships, and friendly interactions changes lives.

He believes the country is suffering from “a crisis of the social fabric.” He sees the hope for humanity in communities’ picking up communities thereby building a “denser moral fabric.”

He knows we are divided by education.

He feels our need for personal relationships.

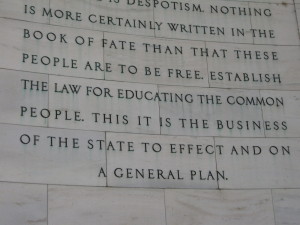

He sees how both Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln supported “limited but energetic government to enhance social mobility.”

But my theory here is that David Brooks can’t see how education reform policies are destroying our social fabric. There’s a couple of reasons. One, A Nation At Risk (in his own words) marks his involvement with education reform. And two, if you view education reforms from a narrow political perch you can easily fall off. If you fall off, you can’t see far enough back to clearly view the road to educational quality and equality. You can’t see our history.

But, let’s consider the education reform road he, and the nation, traveled.

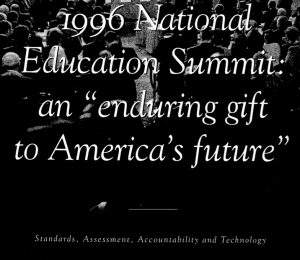

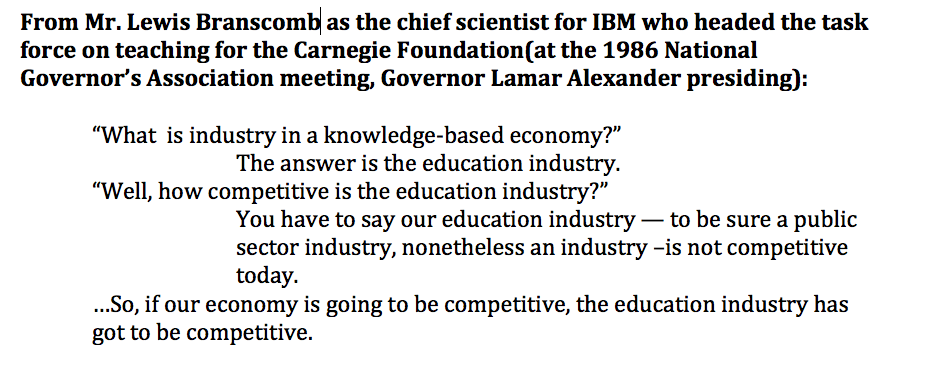

After the release of A Nation At Risk in 1983, there was a flurry of media sound bites unleashed on the public (more propaganda than substance). But what followed is what really set the stage for standards, assessments, accountability, and technology to be the education reform “gift” from the National Governor’s Association (NGA) and others. (See the fine print below.)

In the decades that followed, many attendees of this 1996 Education Summit remained major players in education laws that govern our public K-12 system. That reality did not change with congress’ newest law – the Every Student Succeeds Act – ESSA. “They” pushed the law into existence. They rule.

Their governing philosophy —the foundation upon which they built our reforms— is that we were entering the information age and the economy was dependent on dollars flowing into the education “industry.”

The fact that the majority of parents were satisfied with their child’s school drove the need to wage a propaganda war on public schools. “They” needed to create a market. (To Market to Market, 1997)

Keep in mind, changes in education take roughly a decade to unfold. During the period prior to the standards, assessment, accountability, technology movement, the United States was making significant educational progress in our K-12 system. This was also a time when our higher education was still the most highly revered in the world.

What the hell were we thinking?

Fast forward to post-9/11 of 2001 when David Brooks wrote One Nation, Slightly Divisible. He talked about the education gap and how the income gap had widened as we entered the information age (aka knowledge-based economy).

And in 2005 Mr. Brooks noted the maturation of the information age, in The Education Gap, as he linked “economic stratification” to “social stratification.” He documented behavioral differences in divorce rates, smoking, exercise, voting, volunteer work, and blood donations linked to educational attainment. Stating that this might be a “more fair” (?) system, he acknowledged that the system was creating

“brutal barriers to opportunity and ascent.”

A couple of months later (and four years after No Child Left Behind), Brooks noted in Psst! ‘Human Capital’ that…

“When President Bush proposed his big education reform, he insisted on tests to measure skills and knowledge…. No Child Left Behind treats students as skill-acquiring cogs in an economic wheel, and the results have been disappointing.”

… Brooks saw skills and knowledge as superficial components. And he went on to mention one of our “classic” government studies…

“…James S. Coleman found that what happens in the family shapes a child’s educational achievement more than what happens in school.”

So despite recognizing inadequacies and the misdirection of the No Child Left Behind law, ITS GOVERNING PHILOSOPHIES REMAIN IN PLACE — student outcomes as measured on standardized tests continues as the basis of our “accountability” mechanism?

Call it fed-led or state-led; it doesn’t matter. The nation doubled down on it…quietly.

And in 2009, David Brooks got caught up in the frenzy of “standing up to the teachers’ unions” as expressed in The Quiet Revolution. He, and many other Republicans across the country, jumped on-board the Democrats’ Obama/Duncan bandwagon of what they were calling “real education reform” — coupling student outcomes and teacher pay.

Never mind that test-based accountability didn’t yield real reform.

Never mind that family and other social supports are extremely important to student success in life. … regardless…

…the Quiet Revolution was celebrated.

By 2010, many involved in the American education reform war declared that Teachers Are Fair Game. Many people still believe that the major problem in education reform is that union rules “protected mediocre teachers.” I know many of my representatives here in Idaho do. But the vast majority of American parents don’t see their children’s teachers as the problem.

Time to Reflect, Reconsider, and Respect the Evidence?

By 2005, the country recognized the major faults with No Child Left Behind (NCLB). But it remained the education law of the law for an additional decade. The name was finally changed to the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) but these guiding principles (the major problems with the law) remain in place…

- yearly standards-based, test-based accountability,

- the push for “personalized” learning through technology instead of supporting better teacher-student personal relationships, and

- “choice” through funding of charter schools (which has been sold to us in the name of “parental engagement,” “flexibility,” “competition,” “free-market,” “a civil right,” and “equality of opportunity” to name a few). It’s the ultimate education-real-estate market.

We know what doesn’t work but we’re being pushed into more of the same through the rules that govern our schools —federal, state, and local.

Consider This: Our Common Ground

In 2001 in One Nation, Slightly Divisible, David Brooks asked; Are Americans any longer a common people? Do we have one national conversation and one national culture? Are we loyal to the same institutions and the same values?

According to his research, we agree “too many children are being raised in day-care centers these days.”

You see, we do value family and support the ideal of family.

In The Education Gap (2005) he stated that we “believe in equality of opportunity.”

You see, we do value the ideal of equal educational opportunity as expressed in the aim of the original Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965 ESEA, changed to 2001 NCLB and now 2015 ESSA).

How We Missed Seeing the Trees for the Forest

In keeping with most journalists, Brooks only quoted PART of the work of James S. Coleman. Missing is the rest of the Coleman story.

Brooks touched on the importance of a child’s willingness to learn, which Coleman delved deeply into and discussed it as “the pupil attitude factor.”

Coleman discovered, as Brooks finally did, that a strong community support system for school children is essential to giving every student the opportunity to excel. Coleman dubbed that safety net “social capital” and defined it.

So we do see!

In Psst! ‘Human Capital’ (2005), Brooks expounded on what works.

“The only things that work are local, human-to-human immersions that transform the students down to their very beings. Extraordinary schools, which create intense cultures of achievement, work. Extraordinary teachers, who inspire students to transform their lives, work.”

And by 2015 Brooks looked smack in the face of the solution. He does see. In Communities of Character he talked about …

“super-tight neighborhood organizations” and revealed, “…very often it’s a really good school.” These schools “cultivate intense thick community.”

And earlier this year, Brooks once again brushed-up against a solution to offering equal educational opportunity in The Building Blocks of Learning. About this I write with extreme trepidation!

David Brooks wrote,

“Education is one of those spheres where the heart is inseparable from the head.

Even within the classroom, the key fact is the love between a teacher and a student.

For years, schools didn’t have to think about love because there were so many other nurturing social institutions.….emotional engagement is not something we measure and stress.

Today we have to fortify the heart if we’re going to educate the mind.”

So here’s my reason for concern. Just because something is important to student learning does NOT mean WE should:

- measure it in the children,

- scapegoat the teachers if the outcomes don’t meet our arbitrary standard, and

- make damned sure it is anchored to standards, assessment, accountability (and the technology to do that accountability) in our laws!!!!!

Stop already!

We know functional communities are safer, healthier, and better educated. The people in those communities instinctively understand the concept of a strong social fabric and supporting the common good.

Dysfunctional communities don’t get it. Their safety net does not include the strong fabric of our common good. And standards, assessment, accountability, and technology are no substitute for increasing the resources necessary to supply the proper and necessary fabrics.

“Better policy can help.” We need education reform laws that are free from the dirt and stench left behind by the education reform vulture-capitalists. Does the nation agree?

And are David Brooks’ views on the common good and education reform policies conflicting to others, or, do they clearly echo the sentiments of the nation?

“We” should have a national conversation about that!