The child left behind isn’t always obvious.

The obviously educationally deprived children have been well documented—repeatedly. They are represented by the demographic categories (disaggregated data) of No Child Left Behind in an attempt to bring attention and resources to those groups to correct their education deficit. But in this plan, have we stopped to observe what we have created, to assess what is happening and ask, who is the child left behind and why should I care?

History, experiences, research, and common sense tell us that well-educated people are better able to resist political oppression, live longer and healthier lives, and are less likely to be incarcerated or require long-term social services.

History, experiences, research, and common sense tell us that well-educated people are better able to resist political oppression, live longer and healthier lives, and are less likely to be incarcerated or require long-term social services.

- We obviously believe health care is an issue worthy of our attention.

- We all have heard that our country throws more people in jail on a per capita basis that most others.

- We talk about the importance of an educated, informed electorate.

We seem to comprehend educations’ importance to issues important to us. Yet on the subject of our education system, we fail to be up in arms when we most definitely should be.

2007 is when No Child Left Behind should have been updated or trashed. That date came and went with people across the country complaining —but no wide-spread action was taken en-mass. Our inaction spoke volumes. It told the Powers-That-Be to do with this law what they will. They did nothing.

And worse still, they continued to use a very narrow set of statistics to decide the fate of children across this country. But what if yours wasn’t or isn’t “statistically significant”?

The child left behind is the child that falls through the cracks. And during the Great Recession, our economic decline in most states translated to budget cuts for education. The cracks got wider. In the past, today, or in the future, there is a very good chance the child left behind is in some way related to you.

And we, as a society, we have failed to provide safety nets for children in far too many instances. So in addition to asking who we are leaving behind, we have to ask “Why?” We can not remedy a problem when we won’t face the causes. There are many but none of them are so huge and impossible that they defy our understanding—if we care enough to try. None of them are so costly that we can’t afford to fix them. We have reached the point where we can’t afford not to be successful in improving public education.

As individuals, we must rethink our priorities given the fact that the child left behind may not be who you think it is.

The child left behind can be in any demographic group. The child could be white, middle-class, and English-speaking. If this child is also quiet and well-behaved, the possibility of falling through the cracks is very real and likely. Many a child cursed with being “nice” and “average” has gone that way. This is the child that will be “statistically insignificant” and these cracks are widened by larger class sizes and less individual attention.

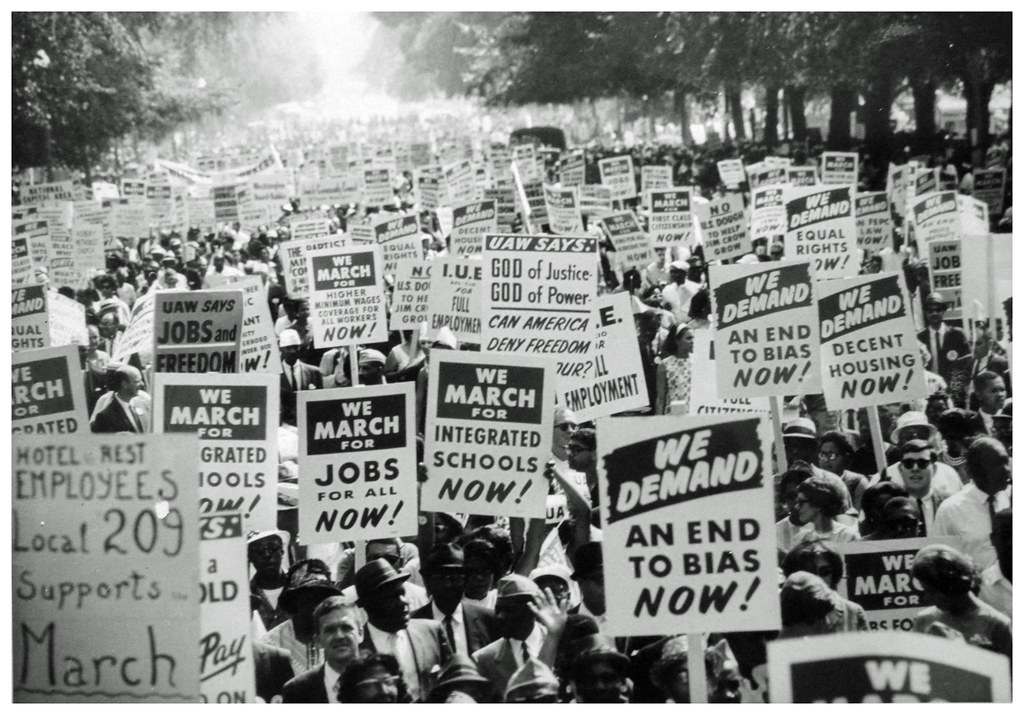

That is a fact. It isn’t stated to take anything away from the dire need to address the children on whom the original Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) focused. That law meant to supply additional funding for impoverished children targeted specifically for teacher development, instructional materials, support programs, and parental education.

The No Child Left Behind version of ESEA established a very different aim — closing the achievement gap. The result has been more funds spent on tests and data collection leaving less money for individual educational needs. And that is why we should all care about getting ESEA right.

It is only through addressing individual needs that we will offer access to quality education for all children. In other words, offering equal educational opportunity means truly leaving no child behind.

Closing the achievement gap is a standards and testing across-the-board attempt to give us the “right” numbers. Offering equal opportunity is the promise of America. Fulfilling that promise is the right thing to do and now is the right time to do it.

Sunset No Child Left Behind; Roll Back ESEA.

UPDATE: No Child Left Behind was renamed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) on December 10, 2015. The problems with the law remain. It’s not right.