Leaders, Civil Rights Leaders, People, what are we missing?

And how is it we don’t seem to understand that “narrowing the curriculum” translates to lost opportunities to learn — particularly in impoverished communities? Those communities were the ones previously targeted by the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA/NCLB). Those schools were the reason ESEA exists.

Federal education law did not come into existence to dictate testing.

Federal education law did not come into existence to dictate testing.

So here are some facts that seem to be missing in the discussion of yearly standardized testing as it applies to reauthorization of No Child Left Behind/now the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESEA):

The original ESEA set this goal.

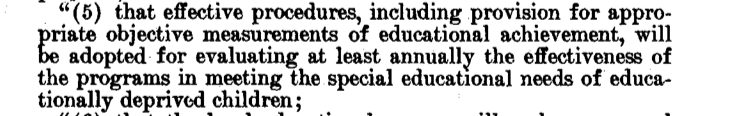

The only “accountability” and testing associated with this law was this:

“Appropriate” was to be determined by focusing on what children need to learn and staying focused on the “educationally-deprived” children.

Measurements of progress were used to assess effectiveness of federal dollars in meeting children’s learning needs. As one citizen recently expressed to me, these were state and locally created “measures.” …But back to the past,… in 1966, the first review of ESEA was released.

Yearly, the council was required to advise the president and congress. This council focused strictly on the children the law intended to help and advised we do the same.

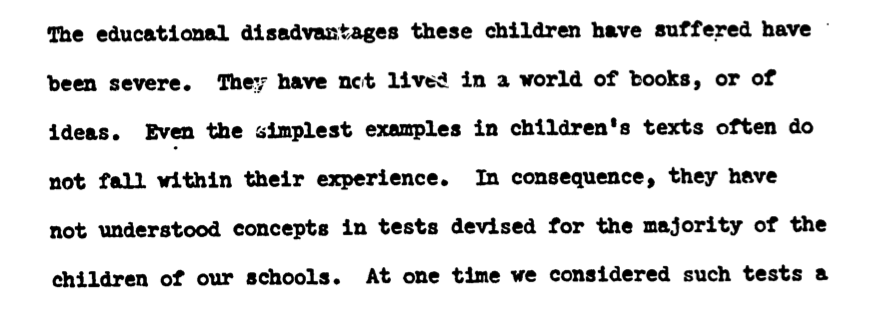

This assessment of the problem, by this council, highlighted their thoughts on standardized testing.

This council understood that these children were coming to school already “disadvantaged” when it came to standardized test scores. Out-of-school factors played a role.

In other words, commercially designed standardized “achievement” tests point at opportunity-to-learn gaps.

Variation within a school is greater than between schools. We have to think about children from low-income families as children with fewer opportunities – unless their community provides them more.

Also in 1966, the Coleman Report said that family background and socioeconomic factors play a role in “achievement” – but it was interpreted to mean that “school resources” don’t matter.

However…….a point made in The Coleman Report that really is what makes the difference between great schools and mediocre ones is the concentration of poverty….if not properly addressed.

Fortunately, the 1965 ESEA was designed taking into consideration both in-school and out-of-school factors and later research by James S. Coleman would prove that an out-of-school safety net of opportunities (social capital) was a factor behind the success of the private Catholic schools that he studied. But as the story of testing goes….

Analysis and intervention must be focused on student learning – in the school where variability between students is largest.

Convinced that all students can learn, Ronald Edmonds looked at schools that began seeing student success regardless of their high-poverty rates. He not only analyzed the common factors in these “effective” schools, he looked at what they did to improve.

Edmonds did not shy away from standards and testing but his bigger focus was on instruction and learning….in the school.

Good-quality teacher-created tests focused on learning objectives in line with clear, locally acceptable standards should be considered as the alternative to yearly commercially-created standardized tests. Then, what gets taught gets tested.

So in light of the fact that the role of the federal government is to ensure our civil (citizen’s) right to equal access, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) is one appropriate tool for assessing national or state achievement/opportunity gaps. We should not change something that has worked well as one indicator of our nations slow but steady progress.

Today, we must consider looking at the real core of the problem that national civil rights groups are having with the idea of giving up yearly standardized testing. We need to consider: when the biggest variable is within a school, when success is really defined by individual student success, student success can only be measured at the school level. The “accountability” measure must be determined by parents, teachers, and communities. Monitored by NAEP to assess inequality, yes. But any further national testing for this reason is not justified and is an overstep.

In federal program evaluations to satisfy “accountability” for dollars, the same data (measures, assessments, indicators) that are used to identify a problem should be used to determine whether the problem has been reduced or eliminated.

And one last lesson from the past that we may have missed, from No Child Left Behind, was that yearly standardized testing narrowed the curriculum to what was tested – it did harm – and instructional time was lost because of test preparation. Limiting learning opportunities in schools is most devastating for children whose parents can’t make up for those lost opportunities. I know this because I saw it with my own eyes.

I hope in the weeks to come that a set of meaningful indicators of educational quality and opportunity come out of the legislative debate on ESEA reauthorization. Yearly standardized achievement tests for all students should not be among them.

#TruthBeTold The civil rights movement marched on a different path to obtain equality in educational opportunity.

Congressional representatives, particularly those charged with re-writing NCLB, do you understand?

(UPDATE: they did not demonstrate understanding when they changed NCLB to ESSA – the Every Student Succeeds Act)

We are at a crossroads where the standards movement that has dominated education policy since the 80’s intersects with the almost forgotten educational history of the 60’s and 70’s that saw the natural progress of effective schools take root because the influential in education policy THEN understood poverty and saw a way that education law could remedy a longstanding injustice – unequal access to quality education.

It is a problem we can solve.