For our republic to survive and prosper, informed citizens are vital.

The importance of informed citizens was clear from the start. And as time has marched forward, there has been a notable commonality among U.S. presidents that dissemination of information is an essential national service. Education matters. The question has always been; how do we do it?

And as time has marched forward, there has been a notable commonality among U.S. presidents that dissemination of information is an essential national service. Education matters. The question has always been; how do we do it?

With the civil war raging, President Lincoln answered in 1862 by signing the Morrill Act establishing the land-grant college system. He said at the time:

“The land-grant university system is being built on behalf of the people, who have invested in these public universities their hopes, their support and their confidence.”

Fifty-two years later, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Smith-Lever Act that established the cooperative extension system for disseminating practical applications of research findings from the land-grant colleges to the people who needed the education.

President after president has acknowledged the success of that dual system including President Ronald Reagan as stated in A Nation at Risk.

“The American educational system has responded to previous challenges with remarkable success. In the 19th century our land-grant colleges and universities provided the research and training that developed our Nation’s natural resources and the rich agricultural bounty of the American farm.”

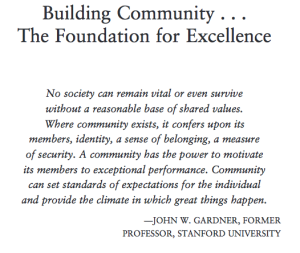

So, I personally am left wondering if President Reagan was unaware of the intentions of President Johnson (D) and his secretary of health, education and welfare, John W. Gardner (R), to model educational and community improvement after our successful programs in agricultural education.

“In July 1964, John W. Gardner, then president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, headed a presidential task force that proposed establishment of the RELs [regional educational laboratories] as a vital link to interpret, shape, and communicate the centers’ research findings; tailor them for practical school use; and infuse them into the nation’s classrooms, including college classrooms.”

So as President Johnson set out to address the issues of poverty simultaneously with those of the education system, he saw the need to provide services for children that would “be adapted to meet the pressing needs of each locality.” He urged that we “draw upon the unique and invaluable resources of our great universities to deal with national problems of poverty and community development.” And it was envisioned that the university extension system could help the people to help themselves. Dissemination of information was seen as essential to improvement.

Dissemination of information was seen as essential to improvement.

As envisioned by the main architect of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Francis Keppel, a network of regional educational laboratories was written into law. As Keppel expressed, they were “designed to serve education much as the agricultural experiment centers long served and stimulated the development of agriculture.”

He felt this would bring together schools and school systems, link proposal to practice, to provide “a missing link.” They were to be the key to maintaining informed citizens.

Today we have ten regional educational laboratories, but they are not serving as originally intended because their marching orders have changed with the changing of ESEA.

“During the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty, the centers and laboratories were intended to be a network of institutions designed to revitalize American education through strategic research, development, and dissemination of new programs and processes. Since their inception, such external issues as the federal role in education and the allocation of funding, along with such internal issues as the challenge of applying research to real-world school settings, have significantly affected the mission and operation of these institutions.”

But despite all the changes and difficulties, the regional educational laboratories have put out some excellent research. However, the goal of forming a network to freely disseminate information and assist in training at the local level was never fully realized and has left us with pockets of schools in need of improvement but without the knowledge and skills to do so. We say they “lack the capacity” to improve. We lack informed citizens.

The regional educational laboratories were intended to provide practical solutions to the issues facing schools. They were to serve as the bedrock of excellence. The information they provided was then to be disseminated to the schools and the general public— free of charge, for the most part. They would be supported by the public system. Flow of information needed to be in both directions ensuring that researchers were addressing what the stakeholders needed to know and be able to do.

When financial support for public research institutions is cut and private interests start picking up the tab, the integrity of research is potentially compromised. At what cost?

We currently have the system backwards — top-down, outcome-based, data-driven instead of student-focused, needs-driven local improvement.

General diffusion of knowledge, dissemination of information continues to be a recognized problem.

As President Carter established the U. S. Department of Education in 1979, the importance of dissemination of research findings was written into the purposes of the department with a few little words— to “share information” (#4).

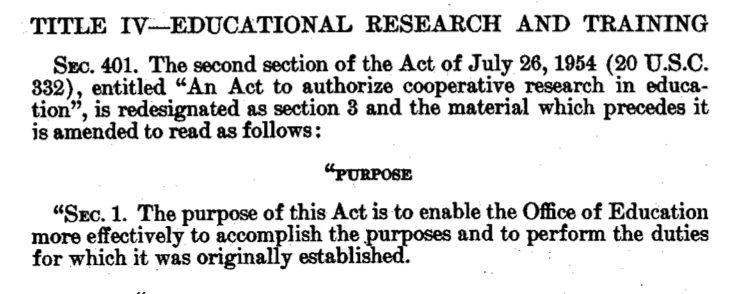

Diffusion of knowledge, dissemination of research findings, sharing information — whatever we call it — the concept once held such importance that it had its own title in ESEA. We once understood the significance of a national system for providing affordable practical education, doing basic unbiased research, and sharing practical, useful information for improvement purposes. And it worked!

We once understood the significance of a national system for providing affordable practical education, doing basic unbiased research, and sharing practical, useful information for improvement purposes. And it worked!

“Land-grant campuses collectively enroll more than 4.6 million students and have 645,000 faculty members. They conduct two-thirds of the nation’s academic research and charge a third as much as comparable private universities, even after years of price increases.”

…. “If a Congress fighting a civil war could pass the Morrill Act, I don’t think the fact that, today, Washington is so divided should stop us from recommitting to it [the land-grant system].”

Preserving, strengthening, and improving this part of the system is essential to K-12 improvement…And it is not clear from either the House or Senate versions for ESEA reauthorization that Congress sees the importance in dissemination of information and its significance in cultivating an informed citizenry. #DoSomething

Tell Congress to go back to the drawing board NOW! This country has waited way too long to end No Child Left Behind and get back to a law that works for US!

(This Call to Action went unanswered because we lack informed citizens. So the Every Student Success Act (2015) -ESSA- became the latest version of ESEA to contribute to the dismantling of the public education system.)